Knowing the Bible’s origins is not just a matter of oure curiosity. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that, either.) Rather, on many occasions it is crucial for proper understanding of the biblical text.

Here is one interesting example.

It is said that seven Greek cities once vied for the honor of being considered Homer’s birthplace. In a similar manner, at least two different cities have been seriously considered as the possible birthplaces of Abraham.

According to Genesis 11:28, 31, Abraham’s family came from ur kasdim – Ur of the Chaldeans; Genesis 15:7 and Nehemiah 9:7 confirm as much. The city of Ur, located in what today is southern Iraq (10 mi or 16 km from Nasiriyah), was a major urban center in ancient Mesopotamia, and one of the oldest. It existed since at least 3800 BCE, and in the 21stcentury BCE it was the center of a large kingdom that controlled much of Mesopotamia (the so-called Third Dynasty of Ur). When in 1922-1934 the eminent archeologist Leonard Wooley excavated the ruins of Ur, finding a lot of exquisite artefacts in the process, he confidently identified it as Abraham’s birthplace, and many scholars agreed.

But not all of them.

Some – most recently Gary Rendsburg from Rutgers University (https://www.thetorah.com/article/ur-kasdim-where-is-abrahams-birthplace) – have pointed to longstanding Jewish and Muslim tradition that Ur of the Chaldeans is in fact the city of Urfa, in the extreme southeast of the present-day Turkey and hundreds of miles north of the site excavated by Wooley. There is even a “pool of Abraham” in the courtyard of a mosque in Urfa.

Rendsburg and others point to a couple of references in the Bible that seem to fit Urfa better than the ancient Ur.

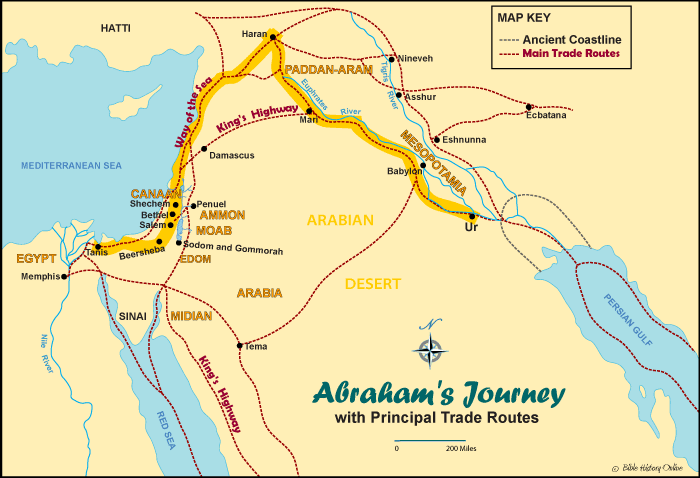

First, Joshua 24:2-3 says that Abraham and his father Terah lived “beyond the River” – that is (looking from the land of Israel) on the left, eastern side of the Euphrates. Urfa is located east of the Euphrates, but the ancient Ur was not.

Second, according to Genesis 11:31, Terah and his family left Ur of the Chaldeans in order to relocate to the land of Canaan but stopped in the city of Haran. If their point of departure was in southern Mesopotamia, where the ancient Ur was located, to reach Haran on the way to Canaan, they had to take a major detour. By contrast, if they departed from Urfa, it would make a lot of sense from them to take the route through Haran (located just 27 mi, or 44 km, to the south).

In addition, Deuteronomy 26:5 calls Israel’s ancestor – apparently Abraham – a “wandering Aramean.” The core Aramean areas were much closer to Urfa than to the ancient Ur excavated by Wooley.

Based on all this, Rendsburg puns that Wooley “pulled the wool over everyone’s eyes.” And he laments that the Pope was on a wild goose chase when during a trip to Iraq he went to the ancient Ur in order to visit Abraham’s birthplace.

But what about the Chaldeans?

This is where the text’s dating becomes crucial.

Based on their language, which is related to Aramaic, Chaldeans come from the general area of Urfa. However, since at least the 10th or 9th century BCE they lived in southern Mesopotamia, precisely where the ancient Ur was located.

In my opinion, the biblical Grand History (Genesis through Kings) was written in its entirety in Babylonian exile, in the years 561-560 BCE. By then, Chaldeans had been firmly established in the vicinity of Ur for several centuries, so the whole area was known as something like Kaldu. Anyone mentioning Ur of the Chaldeans at that time could only mean the ancient Ur excavated by Wooley.

Rendsburg points out that ancient Greek author Xenophon mentions Chaldeans as neighbors of Armenians and Kurds, which would place them north of Urfa. However, Xenophon’s works were only composed in the 4th century BCE, two hundred years after the Babylonian exile. By that time, the term “Chaldeans” had lost much of its connection to a specific ethnic group. In the biblical Book of Daniel, it denotes a profession – astrologers or something like that (2:2, 4). And today a Christian church based mainly in Iraq calls itself “Chaldean” although it has no connection to the ancient population by that name.

Turns out, Wooley did not pull the wool over anyone’s eyes when concluding that it was Abraham’s birthplace according to the Bible. The identification was solid, even more so in fact than Wooley could imagine.

It made perfect sense for someone writing in 561-560 BCE to refer to the ancient Ur specifically as “Ur of the Chaldeans.” In the 620s, Chaldean chieftain Nabopolassar took over Babylon. After the fall of Assyria Nabopolassar and his son Nebuchadnezzar established control over most of its territory, making Chaldean-ruled Babylon the dominant power of the ancient Near East. According to both the Bible and Babylonian sources, in 586 BCE Chaldeans destroyed what was left of ancient Israel: Nebuchadnezzar’s troops overran Judah, and most of its population was deported to Mesopotamia. When Nebuchadnezzar died in 562 BCE, his son and successor Amel-Marduk (Evil-Merodach in the Bible) almost immediately released Jehoiachin, one of Judah’s last kings, from detention, and even invited him to a banquet (2 Kings 25:29-30). To the Judahite exiles it doubtlessly looked as though their captors are finally showing mercy to them that might even extend to Israel’s restoration. What better way to express appreciation than to highlight the fact that Israel’s forefather came from the Chaldean heartland?

If so, what of the biblical references that according to Rendsburg point to Urfa?

Let me take those one by one.

Why does Joshua say that Terah and Abraham originally lived “beyond the River”? Because he thinks of Haran, located way east of the Euphrates. This is where Terah died according to Genesis 11:32, and this is where God first speaks to Abraham in Genesis 12:1 – which would also explain the reference to him as a “wandering Aramean” in Deuteronomy 26:5.

Why do Terah and his family veer to Haran instead of following one of the usual routes to Canaan? In keeping with the time-honored Jewish tradition, I would answer with a question: And why not? They were clearly not heading for Canaan anymore because otherwise God would not have to speak to Abraham in order to send him there. Maybe they decided that Haran would suit them better.

There may actually be an important message lurking here. Both Genesis 15:7 and Nehemiah 9:7 say that God “brought” Abraham from Ur of the Chaldeans, not from Haran. The implication is that although Genesis 11 is silent on the matter the family’s relocation to Canaan was divinely inspired from the very beginning but for one reason or another Terah failed to accomplish the mission. Mindful of that, after Terah’s death God not only spoke to Abraham directly but also threw in a number of incentives in order to get him going.

And finally, if the ancient Ur is the better candidate, why the Jewish and Muslim tradition that the birthplace of Abraham was in Urfa? The answer is simple: by the Middle Ages, when this tradition is first attested, the ancient Ur had been long abandoned and forgotten; it remained buried deep in the sand until archeologists started digging it out in the 19th century. By contrast, Urfa was in those times a thriving major city, a commercial hub. Looking around in search of a suitable location, Jewish and Muslim commentators could not help noticing a name on the map that sounded similar to Ur – and the tradition was born. It deserves respect but based on what we know today about the Bible’s date it cannot be sustained.